What’s Behind the Teacher Strikes?

April 18, 2018

This spring, in an unexpected turn, teacher strikes have dominated the education landscape. In March, West Virginia teachers seeking a pay increase walked out for nine days, and came away with a 5-percent raise. Additional walkouts rapidly followed.

In Oklahoma, teachers garnered a $6,100 (or 16-percent) pay raise and additional school funding even before the strike began; they walked out in hopes of pushing the figure to $10,000. In Kentucky, teachers were protesting a swiftly passed pension-reform bill that includes 401(k)-style elements in the plans for new teachers. Now, Arizona teachers are calling a strike vote, despite Governor Doug Ducey’s proposal of a 20-percent raise over three years.

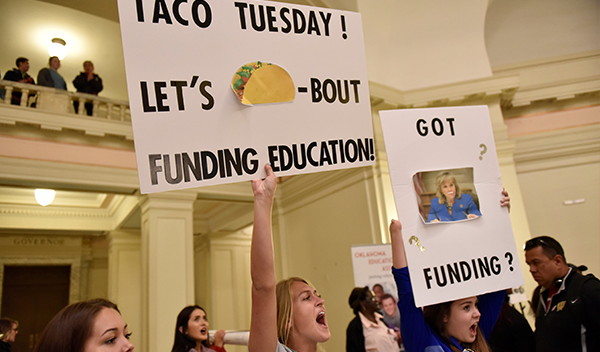

Teachers rally inside the state Capitol on the second day of a teacher walkout to demand higher pay and more funding for education in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, April 3, 2018. Reuters

Why are these strikes happening and what does it mean for schooling?

First, teachers in these states have a legitimate gripe. Their salaries are lousy and have fallen over time. Teacher pay declined by 2 percent in real terms (after adjusting for inflation) between 1992 and 2014. According to data tracked by the National Education Association (NEA), in 2015–2016, the most recent year for which data are available, average teacher pay nationally was $58,353 — hardly a princely sum for a workforce of college-educated professionals. Meanwhile, in the states where teachers have walked out, average pay trails the nation. Kentucky, at $52,134, ranked 26th among the states according to the NEA data; West Virginia ranked 48th at $45,622; and Oklahoma’s 49th at $45,276.

Some analysts, including the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, have blamed the bleak salary picture almost entirely on cuts in state education funding. The CBPP has estimated that Oklahoma cut the state’s inflation-adjusted per-pupil formula funding by 30 percent between 2008 and 2018. This number has been widely cited as the simple explanation for Oklahoma’s travails, in outlets such as the New York Times, NPR, and the Washington Post.

While these cuts are real and significant, there’s more to the story. In Oklahoma, state aid accounts for a little less than half of education funding (the rest comes from local and federal sources). When all sources are taken into account, inflation-adjusted per-pupil school spending was down only about one-third as much as the CBPP suggests — declining 11 percent between 2008 and 2017, according to the Oklahoma State Department of Education.

Moreover, nationally, Oklahoma is an outlier. Indeed, over the past two-plus decades, even as teacher salaries declined across the land by two percent, inflation-adjusted per-pupil spending actually grew by 27 percent from 1992 to 2014. In Kentucky and West Virginia, over that same period, teacher pay fell by 3 percent even as real per-pupil spending increased by more than 35 percent. In Oklahoma, over that same stretch, a 26-percent increase in real per-pupil spending translated only into a 4-percent salary boost for teachers. As has been recently noted of the West Virginia teacher strike, “If teacher salaries had simply increased at the same rate as per-pupil spending, teacher salaries would have increased more than $17,000 since 1992 — to an average of more than $63,000 today.”

Long story short: While it’s not unreasonable to argue that we should have increased school spending in recent years more than we have, it’s a mistake to blame stagnant teacher pay on a lack of taxpayer support.

It also gets tougher to pay teachers more when school systems keep adding bodies — many of whom are “non-instructional staff.” In West Virginia, for instance, while student enrollment fell by 12 percent between 1992 and 2014, the number of non-teaching staff grew by 10 percent. The story is similar in other strike states: In Kentucky, over that same stretch, enrollment grew by 7 percent while the non-teaching workforce grew at nearly six times that rate — by a remarkable 41 percent. And Oklahoma saw a 17-percent growth in enrollment accompanied by a 36-percent increase in non-teaching staff.

Now, additional hiring of non-instructional staff can be a good and sensible thing — even if it’s outstripping enrollment. For instance, educators and parents tend to value the “paraprofessionals” who help in schools. The same is much less true when it comes to central-office mandarins who issue directives and manage required state and federal reporting. But, however one feels about these hires, the simple truth is that, in any organization and line of work, there’s an inevitable trade-off between hiring more people and better pay.

Moreover, while teachers are justly frustrated by take-home pay, their total compensation is typically a lot higher than many teachers realize. That’s because teacher retirement and health-care systems are much more expensive than those of the taxpayers who pay for them — whether those taxpayers work in the private or public sector. As former Obama-administration official Chad Aldeman has noted, “While the average civilian employee receives $1.78 for retirement benefits per hour of work, public school teachers receive $6.22 per hour in retirement compensation.” Between 2003 and 2014, even as teacher salaries declined, per-teacher average benefits spending increased from $14,000 to $21,000, to the point where it constituted 28 percent of total compensation. Of course, it’s also true that a huge chunk of those dollars is going to provide health care and pensions for retirees, which means current teachers don’t see those dollars — even though taxpayers can feel like they’re already picking up a hefty tab.

Speaking of taxpayers, it’s useful to consider how teacher pay stacks up relative to the households that pay their salaries. In Kentucky and West Virginia, even as unimpressive as their salaries are, the average teacher still earns more than their state’s median household income. In Oklahoma, after their recent $6,100 pay raise, the average teacher’s pay will exceed the state’s median household income. Now, it’s completely legitimate for the typical teacher to earn more than their state’s average household and still feel underpaid, but it’s also useful to ponder how some of their demands may quickly start to sow resentment among taxpayers who earn less than teachers do and have less job security and sparser benefits. And that may prove doubly true when many of those taxpayers are parents, forced by teacher strikes to worry about their kids falling behind academically and to scramble to find child care.

School reformers haven’t been much help with any of this. For much of the past decade, would-be reformers pushed states to adopt paper-heavy, test-centric teacher-evaluation systems, while doing nothing to reward terrific teachers, rethink pay, or tackle exploding benefits costs. Even as pension costs swelled — doubling over the past decade — in the wake of the Great Recession, school reformers focused elsewhere. Indeed, the Obama administration’s heralded Race to the Top program discouraged states from using the recession as an opportunity to tackle bloated staffing or benefits costs, both by providing short-term money to prop systems up and by making those funds conditional on not cutting education spending.

Look, teachers deserve to be paid more — especially in places like West Virginia, Kentucky, and Oklahoma. Schools need to figure out how to pay terrific and invaluable teachers more appropriately. Teacher benefits need to be reconfigured so that more school funds are showing up in the paychecks of working teachers, but also in a way that takes care to treat retirees and veteran teachers fairly. There’s a natural bargain lurking here — one in which big pay boosts are linked to rethinking the job description, rewarding excellence, and modernizing benefits systems. Such an approach has a big upside for teachers, taxpayers, and students. Reformers fumbled the chance to pursue something along these lines in the Race to the Top years. Now, when photos of torn textbooks signal stories about “teachers working up to 6 jobs” are going viral, the question is whether we can do better this time.